This past weekend we celebrated the Solemnity of the Most Holy Body and Blood of Christ, which we come to worship in the form of the Eucharist every time we participate at Mass. According to a poll taken a number of years ago, over 70% of Catholics do not believe in this fundamental doctrine—this doctrine, which the catechism states is the source and summit of our Catholic Faith. So, just to set the record straight, we as Catholics believe that at the words of consecration, the bread and the wine at Mass become the real, literal Body, Blood, Soul and Divinity of Christ. The question for us today is, if the Eucharist is so important to us—if it is indeed the source and summit of our Faith—why do most Catholics not believe in it?

I believe there are a couple of reasons. One is that there is a lack of understanding when it comes to the scripture passages that involve the Eucharist. Yet perhaps the greatest reason why so many people do not believe in the Real Presence is because it seems foolish. How can a piece of bread and a cup of wine literally be the Body and Blood of Christ? After all, if it looks like bread and wine, and tastes like bread and wine, it has to be bread and wine, right? Could the Church really be so foolish to suggest that we ought to believe something that contradicts our five senses?

First, I want to start with the scriptural basis for our believe in the Eucharist, which comes from John Chapter 6. After Jesus states that his followers must eat his flesh to have life, the Jews ask, “How can this man give his own flesh to eat?” Here, Our Lord has a perfect opportunity to clarify his command. Yet despite being given the chance to clarify what he said, he doubles down, saying, “Amen, amen, I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood, you do not have life within you.”

In fact, not only does Our Lord double down on his words, but he in fact intensifies his message. In the original Greek text, the normal word used for eating, the way human beings eat, is “phago” (φάγω). However, in the Gospel, Jesus uses the word “trogon” (τρώγω), which literally means to munch or gnaw, in the way an animal would gnaw on meat. It’s a graphic image, but it helped Christ communicate that this Eucharist he is to give us is not a metaphor, but rather real—physically real—in a scandalous way.

I say “scandalous” because the Jews were indeed scandalized. To be scandalized means to “stumble along the way,” and this teaching on the Eucharist was a stumbling block to the Jews, as St. John wrote, “Many of Christ’s disciples returned to their former way of life and no longer accompanied him.” Again, if this was merely a metaphor, Our Lord could have called them back to clarify his teaching. Instead, Jesus turns to the Twelve and says, “Do you also want to leave?”, thereby emphasizing the literal nature of his words.

If it were any other person who claimed it was necessary to eat their flesh to have life, we would rightly label them as insane. However this is Our Lord who is speaking. Even outside of a Christian context, it is commonly agreed upon that Christ was a brilliant rhetorician. Think back to when he was just twelve years old, instructing the doctors and teachers in the temple. The way he taught and the way he engaged the public was nothing short of genius. During my time in seminary, my Scripture professor would often compare how similar Christ’s rhetoric was to the rhetoric of Socrates, the greatest philosopher to have ever lived.

My point is, Christ’s command to eat his flesh is to be either taken seriously, in which case, is consistent with his wisdom, or to be taken as absurd, which would then not be consistent with his wisdom. To disregard his command to eat his flesh is to suggest that, because something doesn’t make sense to us, it must be nonsensical, instead of humbly asking, “What does his command to eat his flesh truly mean? Is it possible that, like his other words of wisdom, he may be saying something profound?”

Yet not only was Christ a brilliant teacher, but he above all proved that his words had weight by dying for his message. He claimed to be God, and by refusing to back down from this claim, was killed for it. There is no greater testimony of a man’s teachings than being put to death for what he taught.

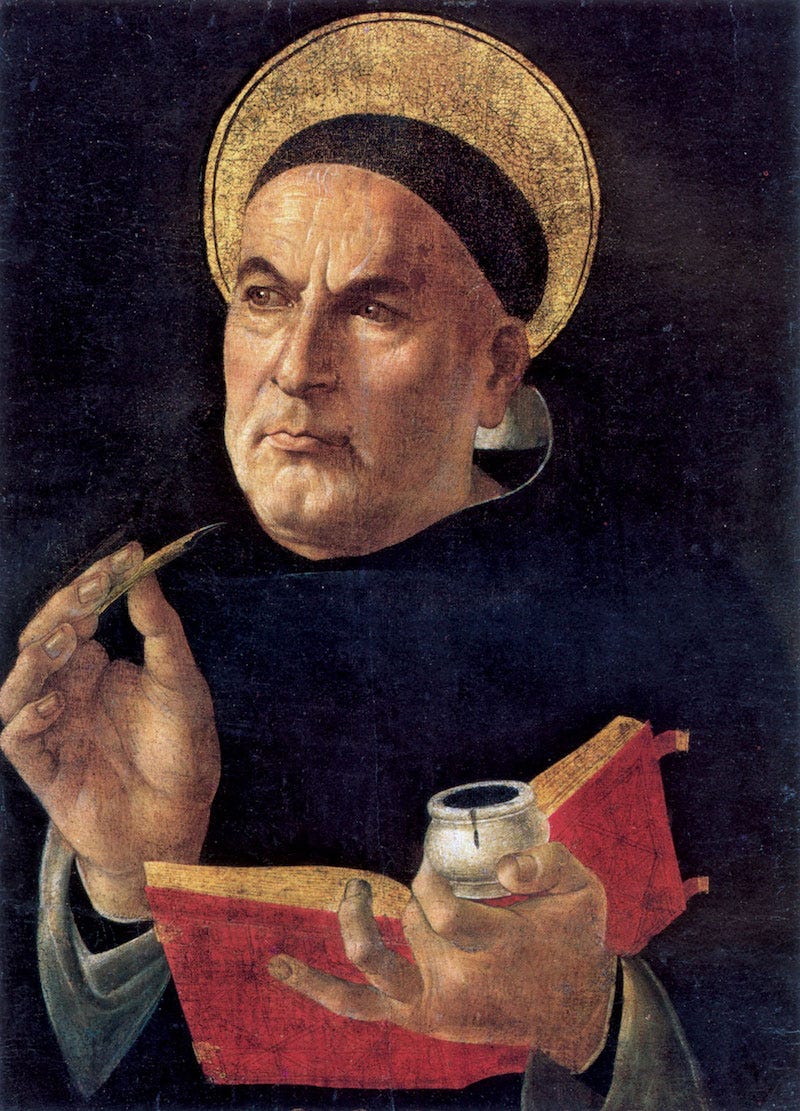

Still, while we indeed trust Our Lord’s words, we as Catholics should not simply shut off our minds and blindly follow everything the Church says. God made our minds to grasp truth, to reason about the things of Heaven and Earth. To shut our minds off and abandon reason is not what the Church intends. Thus while Christians have believed in the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist since the time of the Apostles, great thinkers throughout history have worked in developing ways to understand this doctrine. One of the greatest thinkers who wrote extensively on the Eucharist was the medieval theologian, St. Thomas Aquinas. Aquinas gave us a word that describes what happens at Mass at the time of consecration, which is, transubstantiation.

This word, transubstantiation, can be divided into two parts: “trans” (meaning change) and “substance” (meaning the underlying essence of any given object).

Forgive me for getting a bit metaphysical here, but the lens of metaphysics is the best way to understand the word transubstantiation. So—everything that exists is made up of both matter and form. Take for example a table: a table is materially made up of wood or metal, paint, screws, and so on. Those material things are the table’s “physical make up.” But a table is essentially a table because, beyond the matter, it is simply a table. That is what we call the substance. Though every table may look different (for example, you can have a table with three legs, or four, with a round top, or a square top), all tables are tables because they share the same underlying substance—that is to say, the particular substance of “table-ness.”

To bring this example to the Eucharist, the bread we use at the altar is bread because of its matter—like the wheat flour—and its form (the underlying substance), which is the “bread-ness.” At the time of consecration, what is changed is not the material makeup: it still looks like bread and tastes like bread. Rather, what is changed is the substance: which means that the underlying essence, which was bread before, is itself changed into the Body of Christ. That’s what the word transubstantiation means—that the matter stays the same, but the substance changes.

I bring this metaphysical concept up because it’s my hope to dispel the notion that the Church’s teaching on the Eucharist is ridiculous, something that only uneducated and naive people would believe. There’s a rich intellectual tradition in the Church that seeks to understand this truth on a philosophical and theological level.

Yet still, the question must be asked, why would Christ deem it necessary to give himself to us in the form of the Eucharist? Why must it be his true body and his true blood?

The short answer is because the Eucharist offered to God at Mass is the same offering that Christ made to his Father on the cross, at calvary. If the Eucharist was merely a symbol, then the Mass would be devoid of real sacrifice. It is only through the Mass that we are now able to accomplish what we have been created to do: namely, to offer proper thanksgiving to God.

The word Eucharist is Greek, meaning thanksgiving. The reason we call the offering at Mass the Eucharist—thanksgiving—is because it was Christ who was the first man since the dawn of creation who offered a perfect prayer of thanksgiving to the Father. And because Christ is the bridge between God and Man, we now can follow him and offer our own imperfect prayers of thanksgiving to God, which are made perfect through Christ.

When we come to Mass, we partake in the greatest event in history; we partake in Christ’s perfect offering of himself, which is what saved the world. Again, if the Eucharist was just a symbol—if it was not the real Body of Christ—the Mass would simply be a nice memorial service and nothing more.

However, when we come to Mass, we witness the real offering of Christ Himself to God the Father, which means we are truly present at the event that reconciled God and humanity. Then, if we are worthy by the way we live our lives, we consume him, and become one in him, which is why we also call the Eucharist, Communion. In Christ—in his very Body—we are united as one. And because we consume the sacrificed Body of Christ—the very offering that saved the world—we can say that we consume salvation itself. Again, as Christ himself said, “Unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood, you do not have life within you.” Partaking in the Eucharist is the only way in which we can fulfill Our Lord’s command.

I’ll end here with a quote from the British author JRR Tolkien, who had a great devotion to the Eucharist: “Out of the darkness of my life, so much frustrated, I put before you the one great thing to love on earth: the Blessed Sacrament. There you will find romance, glory, honor, fidelity, and the true way of all your loves on earth.”

Christ has given himself to us in this way. How else can we respond to such great love than bowing down before him in worship?